A Righteous Hajj (Haji Mabrur) and the Challenge of National Glory

A Righteous Hajj and the Challenge of National Glory

“What is the best gift to bring home after Hajj? Is it dates, zamzam water, abayas, robes, or prayer mats?”

Of course, these are all souvenirs eagerly awaited by family and friends back home—and indeed, these are what thousands of pilgrims bring back every year.

There is nothing wrong with that custom. But Hajj must surely be something far more profound than that; something far more spectacular, for a purpose that is equally extraordinary.

What Does Allah Want Us to Gain?

Logically speaking, could it be that Allah simply wants us to feel the heat of the Arabian desert during Hajj? After all, heat exists in many places, including our own homeland. Or perhaps to witness barren mountains, zamzam water, camels, dates, and crowds of people—when, in fact, similar sights can be found elsewhere too? Surely, Allah intends for us to witness something far greater than just the physical landscape.

From an economic perspective, the financial commitment Muslims make for Hajj is no small matter. For example, in 2024, with 240,000 Indonesian pilgrims each paying IDR 75 million, the total spending reaches IDR 18 trillion. That is an enormous sum. Of course, this is not an issue—Hajj is a religious obligation. But the question is: do we view this expense as mere spending, or as an investment that must yield a return? What, then, is the deeper wisdom behind such a massive investment?

In the Holy Cities (Makkah and Madinah), the bustling activities of Hajj drive all sectors into motion. Economic and industrial activities accelerate to support the pilgrimage: food services, transportation, textiles, hospitality, travel, communications, and education—all are mobilized, even on a global scale.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) himself exemplified boundless optimism and joy during Hajj. He journeyed from Madinah to Makkah, Arafah, Muzdalifah, and Mina, followed by 10,000 of his companions, and personally distributed 100 sacrificial animals to the people. A monumental act—imagine this being done over 1,400 years ago.

Let us look back at history. In the late 18th century, in West Sumatra, the legendary “poor pilgrims” (haji miskin) returned from Makkah and triggered major reforms in their homeland. KH. Hasyim Asy’ari established Nahdlatul Ulama, one of Indonesia’s largest religious organizations, after returning from Hajj. KH. Ahmad Dahlan founded Muhammadiyah, also after his pilgrimage. HAMKA wrote Under the Protection of the Ka’bah after his Hajj experience.

These great figures drew powerful energy from their pilgrimage. Upon returning, they initiated breakthroughs that transformed and improved their nation.

The Outcome of a Righteous Hajj: Better Food and Communication

The Prophet (SAW) stated clearly:

“An accepted Hajj (Hajj Mabrur) has no reward but Paradise.” (HR. Ahmad)

But when asked by a Companion what the sign of a righteous Hajj was, the Prophet replied:

“Feeding others and improving speech.”

Here lies the key: food and communication. After Hajj, pilgrims must strive to improve these two things—for the rest of their lives.

Food and communication. The Prophet emphasized them so simply, yet profoundly. Indeed, these are the two pillars of human civilization. There can be no sustainable life without food, and no flourishing civilization without effective communication. As Henry Kissinger said, “Control food and you control the people.” Meanwhile, Alvin Toffler said, “Control information and you control the future.” Food and communication are the essential keys to life and the building blocks of civilization.

From the Prophet’s definition of a righteous Hajj, we can draw the wisdom that the true secret of Hajj lies in its role as a force for improving human life and civilization. Hajj cannot be seen as a purely spiritual ritual disconnected from life, organizations, businesses, nations, or humanity. It must be integral—a spirit, a fire that ignites progress and enlightenment in every sphere of life.

Thus, the cost of Hajj is not a mere consumptive expense—it is a tremendous investment that should drive sustainable development and human civilization forward.

Conclusion

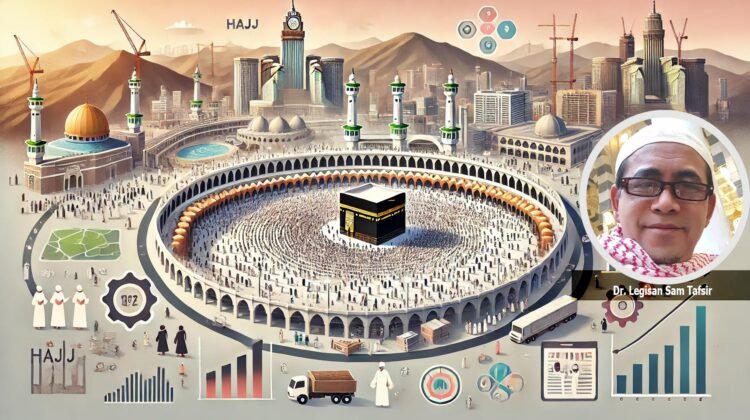

Therefore, the question that pilgrims—and governments that organize the pilgrimage—must ask is: How much return, in terms of sustainable progress and civilizational development, has been realized from the massive annual investment in Hajj? How much has the pilgrimage contributed to the glory of nations and the well-being of societies?

This question is particularly urgent for the Indonesian people. As the country with the world’s largest Muslim population, Indonesia still lags behind—its 2023 GDP per capita stands at only USD 4,700; three times lower than Malaysia’s, and twenty times lower than Singapore’s. Similarly, among the 46 Muslim-majority countries in the world, most still fall behind Western and East Asian nations in terms of development.

With the firm belief that the Hajj is a grand event with deep meaning for life itself, any mismatch between its enormous cost and modest outcome should raise critical questions. It becomes clear that it is the implementation of Hajj that must be reviewed and improved. For indeed, the outcome will never be far from the quality of the process.

Thus, we must ask: to what extent is our Hajj truly proper, aligned with the Prophet’s Sunnah, and fulfilling the divine purpose intended by Allah? Only when Hajj forms great individuals, drives progressive lives, and builds a radiant civilization, can it be said to truly achieve its purpose.

Wallahu a’lam bish-shawab.